Asset-Based Feedback: An Equity-Oriented Approach to Responding to Student Work

By Kent Vi and Sara J. Dozier

Are you wondering how to make feedback motivational for students and less exhausting for teachers? We know that feedback is one of the most effective strategies teachers use for improving student learning. But giving individual feedback for every single assignment for each student is time-consuming, which leads to a long time between when students submit work and when they receive the feedback.

We both use asset-based feedback in our teaching to help with these issues. The goal of asset-based feedback is to see what the students DO understand, as well as any areas that could be strengthened, and to figure out how to support their continued learning. To do this, we read student responses to find patterns of how students are thinking about an idea or concept and give students a chance to make their work stronger. By looking for and responding to students’ strengths first, rather than focusing on whether their responses fit exactly into what we thought we would see, we can help all of our students grow. This is important because our grading and feedback processes often replicate inequitable structures in education.

An example of Asset-Based Feedback from Mr. Vi's high school chemistry classroom:

My students wrote a response to the question "How do icebergs float?" I quickly read 20 student responses and noticed that most responses had something in common. I told the class, "I read your responses yesterday and noticed most of you understood that icebergs float because they are less dense than liquid water. Now, read your own response. If you wrote something similar to this, underline that sentence. If you did not include something like this sentence, revise your answer in a different color so that your explanation is stronger." I provided about 5 pieces of feedback in a similar fashion.

One really cool and unexpected thing many students wrote was "icebergs float because they were only made of freshwater." While it is true that icebergs are made of freshwater, students seemed to be raising the question "Does sea ice sink or float in freshwater?" Because this question came from their responses, the class was engaged when asked to design experiments to test this question. These experiments deepened their understanding of density and encouraged their curiosity. If I had only been grading for correct responses instead of valuing and exploring how students were thinking about science, it's unlikely that I would have noticed this interesting trend and used it to make my instruction stronger.

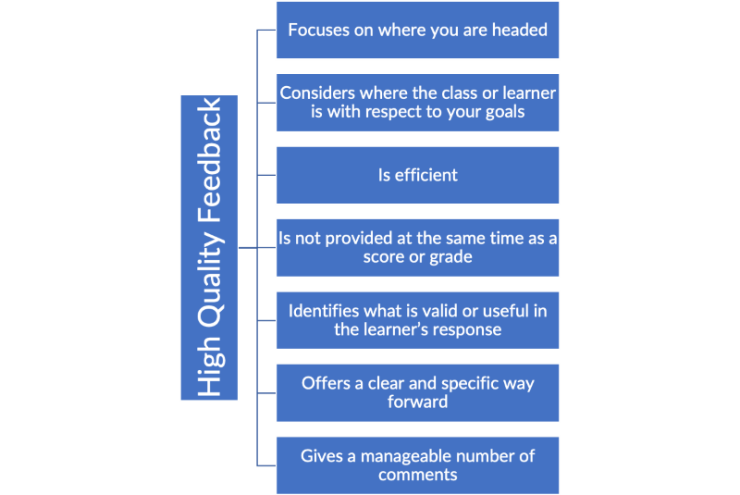

One thing to consider is that all feedback is not created equal. When students receive feedback at the same time as a grade or score, both their interest in the subject and their learning gains are lower. Furthermore, feedback should focus on what a student can do to improve their work on that task. The feedback should be specific and show a path forward. At the same time, you should avoid any feedback that is not about the task itself and compliments the student (e.g., “Nice job!). This kind of “ego-involving” feedback does little to show a student why what they did was effective and leaves them with little information about how to make future progress.

Similarly, feedback should not be simple advice (e.g., “Add more evidence here.”). Instead, high quality feedback should explain why the changes are needed and how to implement them. Finally, if you want students to take full advantage of your feedback, ask them to think about how to make the changes and give them a chance to revise (just like Mr. Vi did). This engages them in a metacognitive practice that helps them interpret the feedback so they are more likely to use it ithe future when they encounter a similar situation.

A diagram indicating components of High Quality Feedback. Components include: Focuses on where you are headed; Considers where the class or learner is with respect to your goals; Is efficient; Is not provided at the same time as a score or grade; Identifies what is valid or useful in the learner's response; Offers a clear and specific way forward; Gives a manageable number of comments

Of course, teachers need to give grades. In this scenario, Mr. Vi collected the work again after giving students a chance to revise their assignment based on the feedback provided to the whole class. We find that grading assignments after they have a chance to revise based on feedback is much faster because the work is of higher quality. Plus, it has the added benefit of allowing students to reinforce their understanding and incorporate new information into their conception of density.

Using asset-based feedback in my classroom has been one of the best changes we have made. Our students respond well to the clear feedback and focus the learning process rather than just the points. This has been more sustainable for us time-wise at giving group feedback and we actually look forward to reading their responses and seeing the creative ways they think about science concepts.

Sources

Butler, R. (1988). Enhancing and undermining intrinsic motivation: The effects of task-involving and ego-involving evaluation of interest and performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 58, 1–14.

Feldman, J. (2019). Beyond standards-based grading: Why equity must be part of grading reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(8), 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719846890

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Wiggins, G. (2012). Seven keys to effective feedback. Educational Leadership, 70(1), 10–16.

About the Authors

Kent Vi is a Chemistry and Physics teacher and has worked at Environmental Charter High School and Saddleback High School. He graduated from UCI in the Cal Teach program in 2014 and is currently working towards a Master of Science in Science Education at Cal State Long Beach.

Dr. Sara Dozier is an Assistant Professor of Science Education at CSU Long Beach. Before becoming a professor, Dr. Dozier served as a science coach at Alameda County office of Education, taught high school science in San Diego USD and San Francisco USD, and worked as a laboratory biologist. Her current research interests focus on equitable classroom assessment practices for science teachers.