Science Education in an Age of Misinformation

By Daniel R Pimentel, PhD Candidate | Science Education

Today, students turn to the internet for information about a range of science-related issues, like COVID variants and climate change. However, misinformation (misleading information shared by mistake) and disinformation (fake information shared with the intent to deceive) can spread easily online. Moreover, science misinformation is often bolstered with fabricated or cherry-picked evidence, making it difficult to determine what or who to believe.

Evaluating science claims on the internet requires the ability to evaluate the credibility of sources. However, evaluating credibility is not often a focus in science class.

How can science teachers prepare students to evaluate science information on the internet? We outline a toolkit of fact-checking strategies and ideas about the social process of science that we think will help.

Fact-Checking Strategies.

The first fact checking strategy is “lateral reading”, which involves opening up new tabs in a browser to research information about any individual or organization making a scientific claim. Opening up new search tabs is a great start, but students will also need to be taught how to search effectively. A second strategy, “click restraint”, involves practicing patience and not automatically clicking on the first search engine result. Search order is not a good indicator of credibility (ads appear at the top of searches, for example). Instead, students can be taught to glance through the URLs and short snippets of information in the search results to get an overview of what multiple sources are saying before they decide what to click. A third strategy, “Use Wikipedia Wisely,” acknowledges that Wikipedia can be an invaluable tool when fact-checking. Rather than avoiding Wikipedia, students should be taught how to use Wikipedia as a waypoint to other sources by investigating the references cited on Wikipedia pages.

Science as a Social Process.

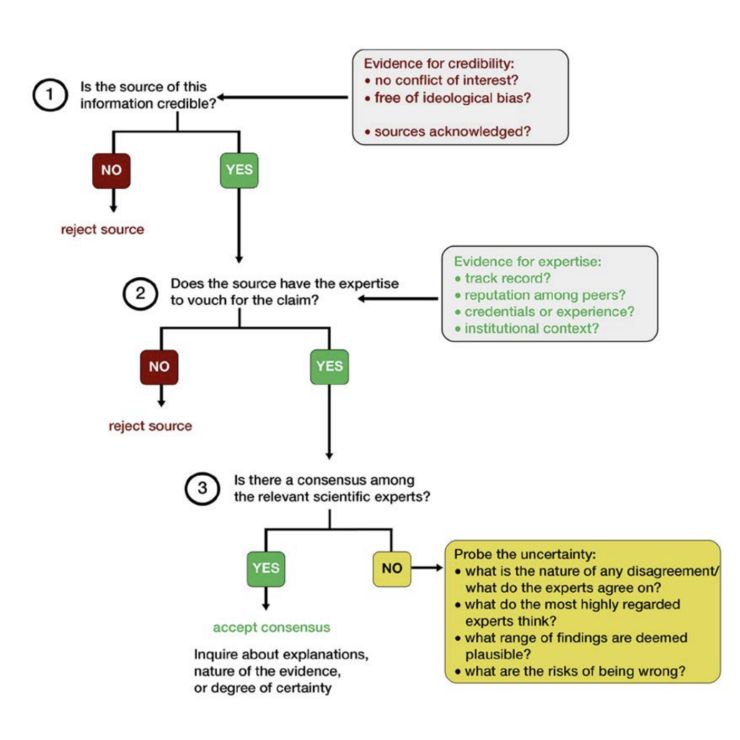

Students also need to know some ideas about science as a social process. When asking the question, “Is this source of information credible?” one important idea is that science often requires funding. By investigating funding sources, students can learn to examine whether or not a source might have financial conflicts of interest. Second, students need to learn about the role of expertise. Science is a highly specialized activity. Being an expert in one science does not make that person an expert in all sciences. By teaching students about the importance of relevant expertise, students can evaluate a source by asking, “Does this source have the expertise to vouch for this claim?” Finally, and perhaps most importantly, students need to learn about the importance of scientific consensus. Relevant experts come to a consensus when they can generally agree on interpretations of data. Students should be taught to ask the question “Is there a scientific consensus on this issue?” and to evaluate claims by determining if they align with the scientific consensus.

By asking all three of the questions about science as a social process (see also Figure 1) and investigating them with fact-checking strategies, students will be equipped with tools to evaluate the credibility of scientific claims they encounter online.

More information about this work can be found at https://sciedandmisinfo.stanford.edu/

Daniel R Pimentel

Dr. Jonathan Osborne