Equitable Grading Practices: Empowering K-12 Teachers for Inclusive Assessment

By Melissa Marcucci, CASE President-Elect

What is a good learner? What evidence would show this? How do you know when students are learning? How do students know when they are learning?

Five years ago, at our then principal 's encouragement, my “Physics of the Universe'' professional learning community (PLC) started exploring the inequities that existed in a traditional grading system where compliance, unequal access to resources, and unrecoverable grades were valued above learning, growth, and empowerment. As we began our research and dove deep into conversations about philosophy and practice, we kept questions like these at the heart of our decision making:

- Do compliance points in the gradebook reflect student learning and mastery of standards?

- Is bringing in cans for a food drive to earn extra credit an equitable practice?

- Is it fair to send homework home with a student that doesn’t have the resources at home to complete the work (internet, school supplies, parent accessibility)?

- What is the difference in abilities and knowledge for a student who receives 59.9% of the points vs 60% of the points?

- Is it fair that 59.9% of the 100% system values a failing grade?

- What does a system that values learning and the learner over the above look like?

- How can we measure true learning? How will our students know where they are in the learning continuum?

Over the next three years, my team made A LOT of mistakes but also learned more than we ever could have if we hadn’t tried new things, asked students how they felt, and revised our practices to meet their needs, encourage their growth, and to provide both equity and access to the rigor set forth in the NGSS. We also read “How to” literature and attempted different ways of designing proficiency scales, formative and summative assessments, rubrics, student self-assessments, and reporting grades in the gradebook. We created videos and documents for parents, students, and counselors to use to understand the philosophical and physical changes to our system of assessing learning and reporting grades. During this time, my district created a task force to research, plan, and implement equitable grading practices in all classrooms. In only three years, and despite the COVID closures, we’ve gone from theory to implementation in every classroom. So, how did we do it?

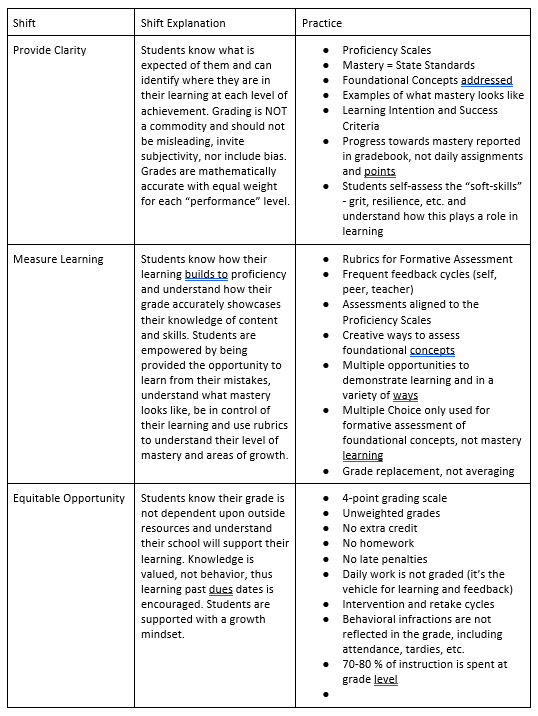

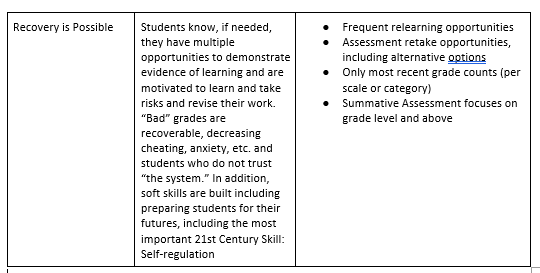

At the beginning of the district-wide efforts, we passed a board policy that all gradebooks needed to be mathematically accurate, thus either 50-100, or 0-4. This provided the clarity to all stakeholders that a traditional grading system is inequitable and we intend to change that and put our students at the center of all learning and reporting of that learning. The district then developed a task force to create deep, meaningful conversations at each site (via staff meetings) using excerpts from current research around equitable grading practices as well as John Hattie’s research showing that self-reported grades have the second highest influence/effect size on student achievement behind collective teacher efficacy. From these sources, we identified four shifts that would be necessary: (1) provide clarity, (2) measure learning, (3) equitable opportunity, and (4) recovery is possible. We spent that year engaged in philosophical conversations of grading at our sites while my PLC continued to make small, quarterly changes towards more equitable grading practices.

The following year, my district task force team worked to put theory into practice. Various sites started their own task force teams to discuss, implement, and reflect on these practices in classrooms. Teachers volunteered to try practices and report out on how it was going. In addition, a cohort of teachers participated in an action research study to dive deeper into their own classroom practices and find solutions that worked, adding ideas to the district task force on where to go next.

We also developed guiding documents titled, “Grading 4 Growth” to support teachers turning theory into practice. The following chart shows some of the practices teachers, including myself, implemented:

We also released teachers from the classroom for two years (2022-2024) to develop, pilot, roll out, and support proficiency scales for the core content areas– science, math, ELA, and social science/history in grades 7-12. K-6 proficiency scales are currently underway, although the K-6 report cards have already been changed to indicate learning. In addition, these TOSA’s will be working with all other content areas (world languages, visual and performing arts, physical education, and other electives) on how to develop proficiency scales for their courses.

The greatest part of our conversations has come down to a few simple things: What is our end goal, and does a particular practice align to this? If given the choice between simple and complex, start simple!! 4-point scale, 6-point scale, 0.5 point increments…it doesn’t matter! Our goal is mastery. Students are either at mastery, above mastery, or below. Focus on what mastery looks, feels, smells, tastes, and sounds like! And then how to get your students there while providing opportunities within instruction and assessment to demonstrate if they are above mastery.

I initially presented some of these efforts at a Science in the River City workshop for the Sacramento Area Science Project where I ran into a former colleague and CASE member, Brian Ellis, who had been considering the same transformations for his classroom. We compared our efforts and presented a session at the CASE Conference in 2022 called, “Putting Meaningful Grading Into Practice.” Some shared lessons learned from our experiences in our own classrooms included:

- Success with meaningful grading practices requires changing some common mindsets regarding assessments

- The most important factor is that students and parents clearly understand the information being reported

- We should remove barriers for students. If they are willing to relearn and retake an assessment, then we should support them in doing so, including informal and/or oral assessments for a small piece of an assessment that needs to be revised.

- Combine similar learning targets/scales together

- Multiple choice questions do not measure the depth of knowledge needed for mastery, but they can be instrumental in formative assessments of students attaining the foundational knowledge and/or skills needed to move towards mastery.

- A well written, 3D assessment measuring mastery of an NGSS standard does not need to be overcomplicated. In addition, students don’t need to answer 10 of the same questions or perform 10 of the same tasks to show mastery, especially if your assessment provides a novel situation. One done really well works!

- All assignments are opportunities to communicate grade expectations and what mastery looks like. Few students may attempt a “Level 4” mastery, but students should always have access to all levels of mastery and know what they need to be able to do and know to move up/over on the continuum of learning.

We are now planning a follow-up session at the CASE Conference in 2023 called, “Putting Meaningful Grading into Practice, Part II” as well as a session at Science in the River City (Sacramento Area Science Project) called, “Meaningful Grading as a Collaboration Tool”.

So I leave you with these thoughts: What is a good learner? What evidence would show this? How do you know when students are learning? How do students know when they are learning?

Resources:

Burns, E., Frangiosa, D., & Bergmann, J. (2021). Going gradeless, grades 6-12: Shifting the focus to student learning. Corwin.

Feldman, Joe. Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms, Corwin, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2019.

Laura J. Link & Thomas R. Guskey (2022) Is standards-based grading effective?, Theory Into Practice

Heflebower, T., Hoegh, J. K., & Warrick, P. B. (2021). Leading standards-based learning: An implementation guide for schools and districts. Marzano Research Lab.

Hoegh, Jan K., et al. A Handbook for Developing & Using Proficiency Scales in the Classroom. Marzano Resources, 2020.

Hoegh, J. K., Flygare, J., Heflebower, T., & Warrick, P. B. (2023). Assessing learning in the standards-based classroom: A practical guide for teachers. Marzano Resources.

Liljedahl, P., Zager, T., & Wheeler, L. (2021). Building Thinking Classrooms in mathematics, grades K-12: 14 teaching practices for enhancing learning. Corwin Mathematics.

Marzano, Robert J., et al. Proficiency Scales for the New Science Standards: A Framework for Science Instruction & Assessment. Marzano Research, 2016.

Marzano, R. J. (2010). Formative assessment & standards-based grading. Marzano Research Laboratory.

McDowell, M. (2018). The lead learner: Improving clarity, coherence, and capacity for all. Corwin.

Redos and Retakes Done right. ASCD. (n.d.). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/redos-and-retakes-done-right

Schimmer, T. (2016). Grading from the inside out. Solution Tree Press.

Taking the stress out of grading. ASCD. (n.d.-b). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/taking-the-stress-out-of-grading

Vatterott, C. (2018). Rethinking homework: Best practices that support diverse needs. ASCD.