The Saga of Cell Phones

By: Stephen Callahan, Maralee Thorburn, and Bret States

When I went to junior high, my father made sure I had quarters in my pocket. After all, what if I needed to get in touch with him? (I might have forgotten my lunch or homework.) And, I needed those to be able to use the payphone in front of the school. It wasn’t until high school that students started having pagers and sending numerical messages. What connectivity!!!!

They were outlawed. Students were not to have them on the school campus. I didn’t really think about if that was right or wrong, it was just the rules. And, anyway, the paper notes we had passed in elementary would get us in trouble too.

iPhone (phone phobia)

The iPhone was released on June 29, 2007. Those of us who have used a payphone probably remember the day. People lined up around the block for a device that promised to change the world. But for a while, it was just a really cool toy and some of the kids had it. They could play mp3s (music), send emails, and take 2-megapixel photos (https://www.cnet.com/news/original-iphone-review/).

Some schools responded by banning technology. There were reasons for this. Among other things, there was a concern that students would be paying attention to this new toy instead of listening to instruction.

A study published recently in the journal Educational Psychology showed a drop in student test performance for those with cell phones present while the lesson was taught. Another study published in Computers in Human Behavior showed that students distracted by cell phone texts performed worse when quizzed than those not distracted during the lecture.

Phone ubiquity (phone acceptance)

We are more than a decade and more than 10 versions later. Pew’s first survey of smartphone ownership in 2011 found that 35% of Americans owned smartphones. This past June they published findings that 81% of Americans have smartphones, with 96 percent owning some kind of cell phone (https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/). This type of change is remarkable. As adults obtained phones in ever-increasing numbers, so did students.

Some schools started adjusting their cell phone policies in an age of cell phone ubiquity. In some schools, the previous policy of banning phones gave way to viewing cell phones as tools that could be used for educational purposes.

In the same way that we have many favorite apps that help us do everything from purchase groceries to navigate rush hour traffic, there is an ever-increasing library of apps to help a student’s cell phone replace the pencil box and slide rule.

Apps like science journals by Google allow students to use their cell phone’s sensors as an array of scientific devices. Students can record everything from notes, photos, and sounds, to light level, magnetic field, and acceleration data. All of this can be exported to a spreadsheet.

While we might not think of it, cell phones have access to a full office suite, meaning that a term paper could technically be written by the glow of a cell phone, complete with hyperlinked references and charts generated on the same tiny device. We can also use other devices to connect to our phones via Bluetooth and direct-wired connections that allow students to measure and collect data for future use back in the classroom. This ability makes field trips take on a new meaning when you can go outside with your phone and measure the air or conduct outdoor experiments with your phone. What students can do with their phones is only limited by their imaginations and version of technology perhaps.

Modern issues (digital citizenship)

I remember being at school and learning about safely operating a car. It was the most powerful thing that many teenagers had, and there was a realization by the adults in my life that I needed to be aware of how to operate it responsibly, or disaster would ensue. The cell phone in many ways has become an analogous rite of passage for students. And, because of its undeniable power, there is also a great amount of risk. Giving students skills to learn to responsibly use their phones will help them as they begin to learn about their digital world and for years beyond. Cell phones are not likely to go away in the future, so it is imperative that teachers learn how to harness, not fight, the powers of technology.

I want teachers to have conversations with other teachers about cell phones in the classroom. This needs to happen because, while the possibilities for what students can gain from cell phones in the classroom are great, the risks are great, too.

Futuristic technologies like Google Cardboard and Google Expeditions allow students to travel around our solar system or deep in the ocean in augmented reality or virtual reality. There is also a push to help students know how to be safe and responsible on the internet. There are multiple solutions, one being Google’s Be Internet Awesome. It has lessons and games aimed at teaching responsibility while online and when using technology. These skills for responsibly navigating a digital world are called Digital Citizenship.

Digital Citizenship

A digital citizen is aware of and understands the rights and responsibilities of using technology. Being a good digital citizen means you are able to use technology safely and responsibility in a positive way. Elements of digital citizenship may include:

- Maintain a balance of use with social media and your identity

- Privacy and security

- Cyberbullying

- Communication and relationships

Teaching digital citizenship should perhaps be the first step as we begin each school year. Many schools have already started the task of figuring out where the new computer science standards will fit in among the different grades and how students behave in this new world of dynamic technology. Certainly any lessons on how to be a good digital citizen would belong in any science or math class just as they would a technology class. As students explore STEM careers in school, they will need to navigate their way through the fast changes in technology. Having a good foundation in digital citizenship will help students throughout their academic careers and beyond school as well.

An 8th-grade classroom example:

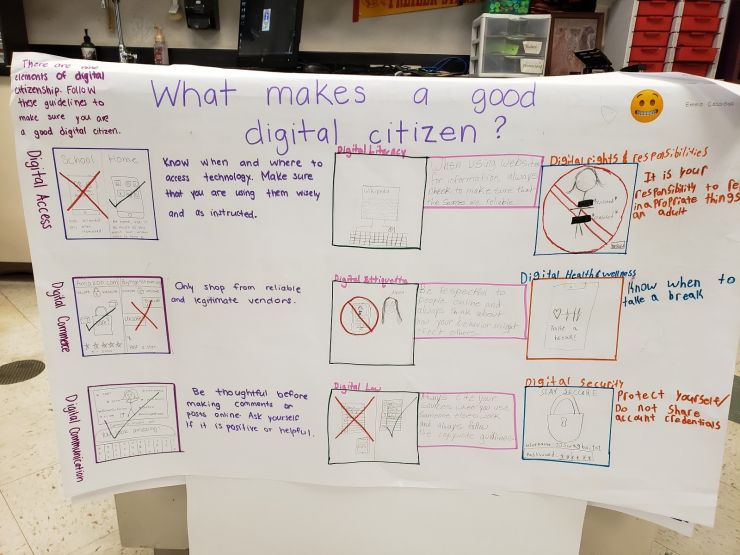

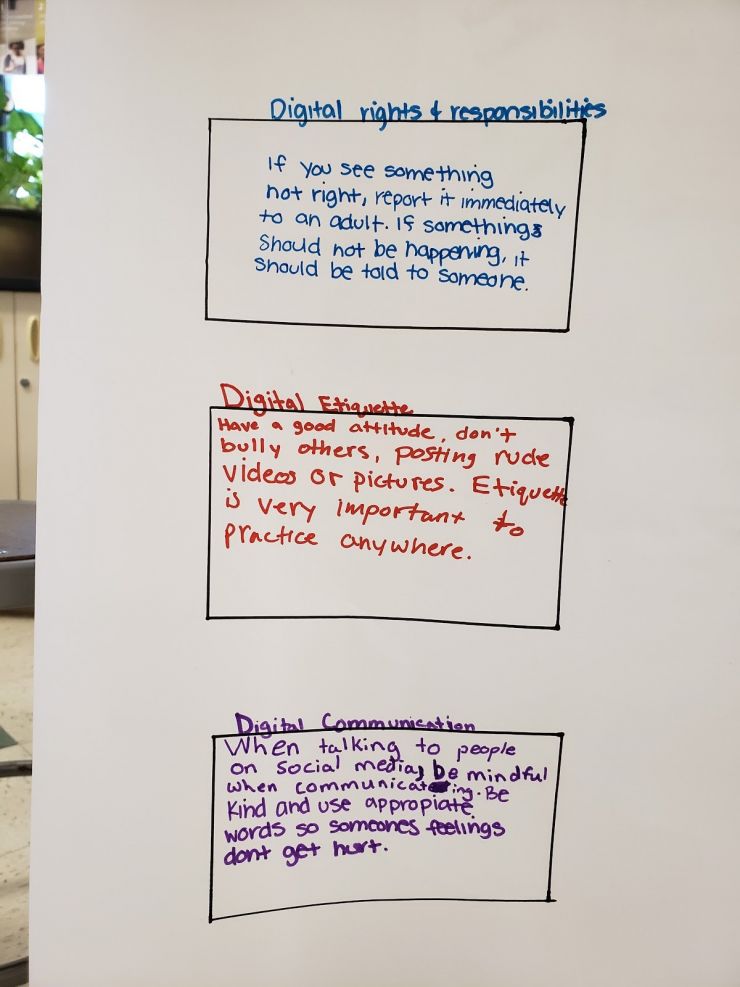

So, over the course of several days, we had discussions about how digital media can be designed with humane or addictive features. I found activities from Common Sense Education (www.commonsense.org) to be very helpful and I decided to have the students create their own guidelines to be a good digital citizen. After discussions and activities, a video, and poster time students presented their guidelines to each other.

Student work samples from posters 8th graders made.

As students presented their posters through a gallery walk, they looked for two guidelines that they already try to follow in their daily lives and searched for two new guidelines that they want to add to their lives. As anecdotal evidence, I knew they were engaging with this topic since they brought it up in another class. How students learn to navigate a digital world is an important skill for them to have. As technology changes, our students will need to adapt, and there is no textbook to help students learn all the do’s and don’ts of being a digital citizen. Where do students learn what is right from wrong? This usually happens at home, but when it comes to being a digital citizen perhaps these lessons should be learned at school as well. The story of becoming a digital youth in today’s world is ever-evolving and never-ending. Start your story in your own class today.

Stephen Callahan is SJCOE Educational Technology and Engineering Design Coordinator,

Maralee Thorburn is a Science and NGSS Core Lead Teacher, Tracy Unified School District and CSTA board member

Bret States is SJCOE STEM Coordinator