Something That a Scientist Does

By Bertha Vasquez, Director, ScienceSaves

I was a science teacher for thirty-four years. On the first day of school every year, I began every class by asking my students to draw a picture of a scientist doing “something that a scientist does.”

I did this with students from kindergarten through twelfth grade. Regardless of age, students inevitably drew an older man often with crazy hair. The scientist almost always wore a lab coat and goggles and was standing next to colorful beakers full of smoking chemicals, as if to say “I’m going to blow up the world!”

As I’d show the drawings to each class, I’d pretend to get upset—Oh, look! A man in a lab coat with chemicals! And another one! And another one! What’s next? Let me guess: a crazy-haired guy with chemicals… The students would giggle and get excited. The one or two drawings in each class that didn’t show that (and there were rarely more than one or two), I would discreetly shuffle to the bottom of the pile to drive my point home later. I’d ask them, Is this really what you think scientists do? Then I’d point up to the air conditioning vents—keep in mind, these classes were meeting in Miami, Florida, and the first day of school is in August. Air conditioning. Electric lights. Microscopes. Computers. All available thanks to science.

“If not for science,” I’d remind them, “half of you wouldn’t be here.” In 1800, almost half of all children died before the age of five. That was before the advent of life-saving vaccines, antibiotics, safe food, water filtration—all the result of caring humans “doing something a scientist does.” We’d then take turns listing many other scientific inventions that have saved lives, made them longer, or made them better.

In a demanding world in which people tend to focus on what is going wrong, it is easy for us to take science for granted. We think of science as a cold, calculating way of looking at the world, somehow robbing it of its mystery. I beg to differ! Science is inspired by wonder for the world around us and fueled by unrelenting curiosity. The work of science can sometimes be tedious; it requires dedication and patience, but the knowledge it has unlocked over centuries is awe-inspiring and transformative.

So how can people see that? Well, one way is by celebrating National Science Appreciation Day every year on March 26.

March 26, 1953, is the date Jonas Salk announced the successful preliminary trials for the world’s first polio vaccine. Since the World Health Assembly resolved to eradicate polio worldwide in 1988, Salk’s breakthrough vaccine has prevented more than eighteen million cases of paralysis and more than 1.5 million childhood deaths. Polio cases have dropped more than 99 percent. Think of the misery and heartbreak that this one discovery has averted. In 2021, only two countries continued to have cases of endemic polio, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

National Science Appreciation Day is an opportunity for everyone to reflect on the power of the scientific method to better human health and life. Given the current state of affairs, where science is facing criticism from different quarters due to the vested interests of some people, it has become even more crucial to acknowledge and appreciate the discipline’s value. It’s disheartening to see some people denying the efficacy and safety of vaccines while others question the scientific community’s integrity by labeling it as discriminatory and biased. These side battles, grounded in ideology not data, erode support for and trust in science. The benefits of science are undeniable. We owe our very lives to it.

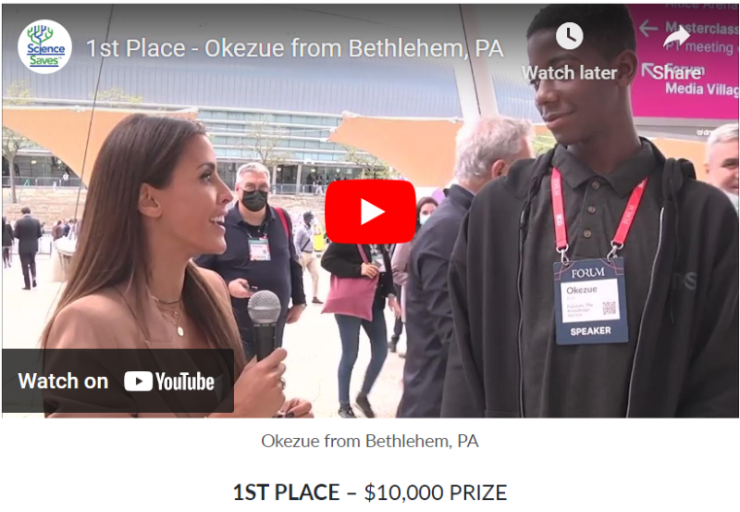

In addition to promoting National Science Appreciation Day, #ScienceSaves offers a $15,000 scholarship contest for high school seniors who create 30-second videos on how science has improved their lives or the lives of somebody they know.

An entire section of the ScienceSaves website is dedicated to providing teachers with free lessons that raise awareness of the positive impact of science in our lives. Many people in the United States may not remember what life was like before the scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century. For example, in 1800, almost half of all children died before the age of five and the average life expectancy in 1900 was only 47 years.

The ScienceSaves lessons are tied to science, language arts, math, and elementary school standards and come with downloadable lesson plans, slide presentations, teacher notes, student response sheets, and rubrics.

During the last week of school, I would ask my students to draw a scientist again. This time, the students drew themselves in many different, real-life scenarios. No more mad scientists! Instead, students pictured themselves investigating the natural world, tracking tigers, diving in research submarines, and crash-testing new lightweight skateboard materials. Over the years, hundreds of my former students have contacted me, many of whom became working scientists. They are living out those pictures in their daily lives—and, in the process, helping change the lives of countless others.

About the Author

Bertha Vazquez recently retired after thirty-four years as an award-winning middle school science teacher in the Miami-Dade County Public School District. She is the director of ScienceSaves, a program of the Center for Inquiry designed to promote appreciation for the value of science.